“You look a right mess – you can’t go on stage like that!”

It was a key night in our faith centre’s yearly calendar and I was due to host and lead our evening programme. Presenting in my second language, I’d spent hours working on the text, ensuring I wouldn’t make any grammatical mistakes. I knew my words mattered. Half an hour before the start I finally felt ready. That is, until my co host took one look at my outfit and exclaimed the phrase above, shocked.

The literal word she used (in her mother tongue) for ‘you look a right mess’ was ‘you look like a shed/shack.’ To her mind, I was about to present in a holy place looking like I was dressed for the farm. It was a huge mismatch. For my friend, it wasn’t just the message but the manner of presentation that mattered too.

To give myself some credit, I’d come dressed in black and I’d brushed my hair. But I hadn’t done that much make up, added any extra pizzazz to the outfit or worn shoes that were especially smart. For my Middle-Eastern colleague, this was all wrong. I’d been so busy looking at my words that I’d become blinkered to other aspects that, for her, were also speaking, sometimes even more loudly, than the words.

It wasn’t simply what I was saying that would be heard, but how I was saying it too: where she was brought up, listening happens with all 5 senses and pays attention to more than just the mouth.

When my husband (a Brit like me) took part in a televised startup investment competition in the Middle East, he was briefed by the organising staff to dress smartly and show his business acumen not simply through his pitched product, but also through the way he presented himself. The organising team told hushed stories of applicants before who had arrived to present in *horror of horrors* shorts and flip flops!

In some Western contexts today it’s almost become a mark of genius to look dishevelled; it doesn’t matter what you dress like, ‘the work will speak for itself.’ Nevertheless, my husband was strongly advised that in this context that would not be the case; the smartness of his outfit would speak not only to the smartness of his work, but also to the level of respect he held towards the attending investors.

Mixed messages are like sound system feedback

My husband talks about the ‘mixed messaging’ of misaligned content and context being like someone speaking through a microphone with feedback squealing through the sound system. You can make out the message but it’s very difficult to focus and the other inputs are hugely distracting.

In some cultures, when the manner and mode of communication doesn’t fit the message, it creates dissonance. When this dissonance is unintended (more about intentional dissonance later), it makes it hard not only to follow what’s being said, but also to believe the content of the message to be true. “You’re saying ‘yes’ with your mouth but ‘no’ with everything else…” or vice versa.

In some cultures, it can be confusing, perplexing and frustrating when the context doesn’t match the content (and vice versa).

One Plate or Many Plates?

It makes me think of mealtimes and the way I grew up eating as opposed to the way many other cultures serve their food. In my UK upbringing (and not true for all, I know), my meal was served to me in one portion on one plate put right in front of me to eat. “That’s yours, eat up!” I sometimes had a side plate for bread, but generally I knew what the meal was by looking at the one plate.

I’ll always remember going to China as a student and inwardly wondering, from the array of dishes on the table in front of me, “which one is mine?” And even, what meal is this? Of course, ALL the plates were there to be enjoyed by everyone at the table. The meal wasn’t just made up of the contents of one plate, but made up of many dishes to be dipped into and enjoyed as a whole.

Eating the meal meant broadening my view to the whole tableful of plates and adopting the style of dipping into all of them. Limiting myself to the one plate in front of me would have completely missed the rich diversity of dishes (and left me hungry!).

This plate principle is at work when it comes to communicating meaning too. For some cultures, there is pretty much ‘one plate’: it’s all about the words.

In other cultures, the spoken word is only one plate of many. In these settings you’ve got to lift your eyes and consider the whole before you know what’s really being served up and communicated to you.

The Multiple Plates of Meaning

Of course, it’s not simply about clothes. Meaning and value can be communicated and carried, and in some cases imbued and bestowed, through many dynamics and markers. Here are a few:

- Body language – how is the body saying things the words are not?

- Touch/not – affection or distaste communicated through touch, greetings, and closeness or distance.

- Posture – when are you relaxed, what or who makes you sit up straight?

- Embodied emotion – how much does the importance or value of something reflect in your face?

- Tone of voice – how is passion or persuasion communicated through volume or tone of voice in your culture?

- Clothing worn – what markers signify weath, rank, respect?

- Position in the room – who sits where and what does this say about them?

- Position of things – where are there sacred places or unclean places in the house or community?

- Age/Experience – how much does the age or CV of the person speaking to you affect how (or if) you listen to them, or the weight you give to their words?

- Language:

- Sayings and proverbs – how is deeper meaning communicated through pictures, parables or shared stories?

- Linguistic modes and markers – how would you address a friend, a boss, an elderly relative? And, how much does your formality of language change according to with whom you are speaking?

What other plates would you add from your own culture or those you have learnt from? Do post your thoughts in the comments below – I’d love to learn and engage in conversation about this.

High-Context v Low-Context Cultures

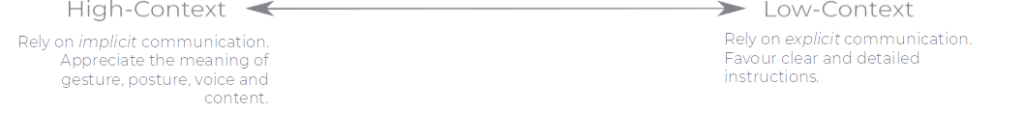

Those of you familiar with the common cultural intelligence scales will recognise that we are talking about the Low-Context/High-Context cultural difference.

I first came across these terms and ideas many years ago through the work of Sarah A Lanier (Foreign to Familiar) and then Philippe Rosinski (Coaching Across Cultures). But I’ve also revisited them recently whilst reading Erin Meyer’s accessible, humorous and highly informative book, The Culture Map.

–

–

When the way you say things and how you say it doesn’t really change that much in any context or situation, and where meaning is mostly communicated through words spoken literally and simply, the culture is considered to be ‘Low-Context.’

Where the means and manner of presentation is a huge part of the how meaning is made and constructed, and might sometimes even appear to contradict or outweigh the words (more on this in a moment..), the culture is considered to be ‘High-Context.’

Have a think for yourself, a group or team you work with or your organisation:

- Where does the family, organisation or national culture you most identify with tend to fit on this scale?

- Think of those you know from other cultures (business, religious, family, national).

- Where do you think they might sit on the scale?

- What difference would it make to find out?

- How could you learn more from them and about them?

Implied v Explained

Rosinski’s idea of implicit and explicit communication is pretty key. While low context cultures value explanation, high-context cultures pick up implied meaning before it’s even voiced let alone explained. Here’s another simple, real life example:

A couple of months back my colleague, Rachel, was teaching us on a topic she was passionate about. Right in the middle of her in-depth explanation, another colleague, Maria, leapt up and interupted her, saying, “Can I get you a glass of water?” Rachel paused, shocked at the interruption (as were we all), frowned and then slowly said, “no I’m fine, thanks…”

It was awkward.

But then Rachel coughed, cleared her throat, turned back to Maria and said, starting to laugh, “You know, actually, you’re right, I would really like a glass of water, thank you so much!”

As we waited for Maria to return with the now highly anticipated water, I replayed the last few minutes in my mind. What had happened? What had I observed?

It struck me that while I had been focussing on the presentation, Rachel had actually coughed a number of times, had once clutched her throat and played uncomfortably with her necklace, had touched her (empty) water glass, absentmindedly, and had shifted a number of times in her chair. Although my brain had registered these inputs (I could remember them when I thought back), my brain had filtered this information as irrelevant.

Maria, however, had observed each signal and ‘put two and two together’; Even though (lower-context) Rachel hadn’t mentioned anything about water, (higher-context) Maria had perceived that she needed one, urgently. So she had acted from her reading of the non-verbal cues.

(It’s maybe also worth noting that higher-context cultures are often also more communally minded. Maria was not only listening with all her senses, but operating from an assumption of her placement to contribute and help. To my more individualistic mind, if Rachel wanted water, she’d get it herself.)

Listening with all 6 Senses

We might say that this ‘putting two and two together’ or reading non-verbal cues doesn’t merely involve our 5 senses, but a discerning intuition to put the inputs together: a sort of cultural 6th sense, perhaps.

Erin Meyer discusses how different countries talk about this 6th sense. The French listen to what is beneath the words (‘sous-entendu’), the Chinese apparently have an ‘art’ of ‘beating around the bush’ to communicate tactfully without being offensively direct, and in Japan they call this wise discerning intuition, ‘reading the air.’1

Just last week some Middle Eastern friends were lamenting about a situation where their colleague from a low-context background didn’t ‘read the room’ to understand the dynamics implicitly at play.

In this scenario, (to come back to the intentional dissonance topic) the Middle Easterners had created an intentional mismatch in their embodied communication with the desire to communicate ‘no’ through action, posture and gesture (majority of signals), whilst still showing respect by saying ‘yes’ with their words (just one ‘meaning plate’ – minor).

Their expectation had been that their lower-context colleague would ‘read the room’ to pick up on the actual meaning, without a distasteful topic needing to be explicitly addressed (how vulgar!). That’s what any Middle Easterner would have done! The positive response (verbal content) combined with the contextual negative signalling (everything else) would be considered as a polite refusal: “no, but thank you.”

However, their low-context boss had taken them at their words, then been perplexed when they didn’t show up, unaware of the loaded table of other indicators of the more accurate, fuller picture.

Adapting to Low-Context Cultures

We’ve spoken about a Lower-Context moving to a Higher one, but of course the reverse might also be true.

Last month I gave a workshop for some interns working interculturally. One attendee had recently moved to the UK from Africa and was having trouble believing that the many signals, gestures and messages she was picking up from British colleagues, might not actually mean anything or be aimed at communicating a message. Back home every signal carried weight.

Erin Meyer quotes a Japanese businessman in the US pondering, “Is it possible there was no meaning beyond Mr Brown’s very simple words?”

Having lived in the Middle East for over 10 years, I also find it hard to dial down my hyper-vigilance to all sensory inputs, and to adopt a ‘does what it says on the tin’ mentality. Even though the UK isn’t even the lowest context culture there is (here hints and gestures are still a key part of communication here), comparatively it’s far lower than where I was.

I still have to work hard to convince myself that direct communication isn’t actually rude here.

It’s hard to accept after living in a rich culture of deeply embedded gestures and symbols, where communication through an intricately and carefully balanced flavours of meaning is the norm, that in some places, basic though it might seem, people do simply just mean what they say: no more, no less.

- Which listening (input) trajectory are you on? Learning to listen to others with all your senses, or figuring out how to believe and pay heed to just a few?

- Which communication (output) trajectory are you on? What would it take for you to communicate more creatively and broadly than simply your words? Or, how might you need to let go of hints, gestures and implied meaning to speak and communicate more explicitly to those who need it?

What are some final takeaways for our teams and processes here?

When Words Fail

One of the best things about living in a high-context culture was that even when our language level at first was poor, there were others ways that we could communicate feeling, fervour, compassion and connection to others. We spoke like toddlers but our words were only one way to communicate; Giving a hug, smiling with our eyes or kissing the hand of an elderly neighbour still spoke a message clearly. Words were only one plate of many and our friends and neighbours were attuned to read our genuine desire, even without us being able to phrase it. (Of course, this is also a warning that if you’re simply paying lip-service to something, people will see right through you!)

Clarify Clarify Clarify

This is right at the heart of all intercultural communication, but particularly where communication is happening through all-senses intuition. It’s possible that the ‘signs’ we think are telling us something a) are not, or b) are telling us something, but not the something we think it is. The old faithful question of “in my culture when someone does that it means this, but is that true for you too?” is not just helpful but essential when we’re reading the air but might not be interpreting it correctly.

On this exact topic, Erin Meyer comments that:

“Multicultural teams need low-context processes.”

Meyer, E. The Culture Map, p55

She’s saying that where a team is trying to decipher unspoken, implicit signalling, we need to earth our communication into clear, explicit processes.

On one level this seems an excellent recommendation.

It’s essential for our teams to be aware of the dynamics of high and low context culture and how that will affect, in particular, the communication patterns of team members and as a group. Some members will always want and need more clarification. Others will have already intuited what’s needed several meetings ago because it seems obvious from context.

And for yet others, they’ll be unintentionally giving or receiving messages that are communicating something completely different to what they are really trying to say (feedback squeals). Even if the team is all from high-context cultures, implied meanings of gestures, social cues and/or non-verbal language might vary hugely between cultures. So what happens when someone attributes a meaning to a gesture that is correct for their culture but not for another?

A low-context solution is to simplify all the processes and make everything clear to everyone.

Maybe the higher-context way would be to take the time to learn about what other plates of communication are on the table and how the team can incorporate some of these ways of thinking, being and operating into how they work. What dress, language, positioning and process might be more helpful?

Perhaps the dream would be to create a team culture that becomes intuitive and richer with unspoken meaning through shared experiences, whilst still remaining explainable to new teammates.

What do you think?

Regardless, it’s important to ask ourselves:

- How might a diversity of contextual low/high dynamic affect the operations of teams you are a part of? How can you, as team leader or team member, be a connector of those who are from different ends of the scale, and facilitate their communication awareness and practice?

Turning Tables, Disregarding Plates

I can’t finish this article without posing the challenge to ignore everything that I’ve just written! Well, not ignore it, but rather to hold it within a broader picture.

It has to be said that sometimes value and importance simply do not conform to our socially understood signs of it.

My Middle Eastern friend was shocked that I had ‘dressed like a shed’ in a faith space. But yet her great faith leader, Jesus Christ himself, was born in a barn. In the Middle East, no less.

Whilst we are called to think about and accept the discomfort of developing how we communicate clearly and effectively in other cultures (becoming higher or lower), yet also, always, need to keep an open mind to where meaning and message are communicated in a way totally extra-ordinary, shockingly perhaps, when compared to our preferred cultural means of communicating.

In other words, while we are called to develop an intercultural fluency in our teams, roles and families, there will still be moments where we are called to spot the important thing, person, situation when it totally confounds (or even offends) our expectations. And to stand with them regardless, even when this makes us misunderstood ourselves.

——

Get in touch if you’d like me to run or speak at a workshop on this or similar topics with your team, organisation or colleagues – awareness and knowledge are the first steps to CQ growth. Employ a coach to help you walk this out into strategy and action going forward.

- Meyer, E. The Culture Map (2015) pp37, 48

Photo thanks to Alex Munsell on Unsplash and Canva

Leave a Reply